Gold has its roots far back into early civilisations and has ever since been one of the most valuable trades across the globe. While gold-digging still exists today, it has however seen a drastic shift in its practices, especially with the advent of high-end technology and precise engineering.

Also read: 10 Great Destinations in Australia’s State of Victoria

At Sovereign Hill, we see one of Victoria’s successful gold rush history, delicately preserved in an outdoor museum in Ballarat. A far cry from the modern-day gold discovery scene, Sovereign Hill encapsulates 19th century Ballarat — the Wadawurrung people, the Europeans, the Eureka Rebellion and most importantly the precious yellow metal that transformed Ballarat from a small pastoral settlement into a provincial city, just a decade following the discovery of gold in 1851.

Optimum preservation is probably the best phrase to describe this open museum. While everywhere else in the city is a reflection of modern Victoria, a step out of the ticketing counter and onto the uneven sandy gravel terrain miraculously pulls you back in time.

Sovereign Hill is huge — it spans across 25 hectares of land, with half of it comprising the outdoor museum and the other accommodating its famous multimillion light and sound show, ‘Blood on the Southern Cross’, and paddocks for its horses.

Yes, horses.

It is, after all, the 1850s, where one of the most popular form of transport were horse carriages. Once you hear the galloping of the horses, the sounds of their hooves against the gravel, look out for them, and if need be, you might need to move to the side to let the carriage pass. Oh and you might come across some horse droppings, so walk carefully!

It is a usual sight to see these beautiful horses in fours pulling a slightly modern version of the 19th century carriage run by Cobb & Co. Coach, steered by a handsome coachman clad comfortably in straight-cut pants and a collared shirt, beneath a vest dusted with a little sand that must have blown towards him as he rode.

In fact, those working and volunteering at Sovereign Hill, both young and old, have all adopted the style and character of the 19th century. While the women walked around elegantly in long bell-shaped skirts, corsets, puffy sleeves and bonnets, the men pulled off their masculinity in tail and double-vested frock coats, straight trousers and top hats.

But before you even get deeper into the museum to meet these lovely characters, you’d be first marvelled by the remnants of the goldfield you have just entered. There is history everywhere!

Panning for gold is one of the popular activities there. A creek stretches across a part of Normanby Street and Red Hill Road, and many visitors are often seen with a gold pan or a cradle, submerging them partially into the water and panning for gold among the other kinds of metals and stones. It has been said that there are up to $50,000 worth of real gold ‘salted’ in the creek, and it is ‘finders-keepers’. In my first but failed attempt at gold panning, I was rather more afraid of falling into the stream than finding no gold at all. The pan, with all the stones and gravel, and perhaps some yellow metal, was heavy!

Gold was first discovered in Ballarat at a place called Poverty Point, now Golden Point, by John Dunlop and James Regen on 21 August 1851, which happen to be the first gold to be found on the rich fields of the Ballarat diggings. Unfortunately, but fortunate for some and for Ballarat, a newspaper man had been following the duo and the news thus spread like wildfire, pulling thousands from all over the world to make a fortune from the richest alluvial goldfields ever known! The following year saw 20,000 diggers and the population explosion led to Ballarat’s proclamation as a town in 1852, a municipality in 1855, a borough in 1863, and by 1970, it turned into a city. It was known that activity at the goldfields were so frenetic that oncoming diggers could hear the clatter of the pans well before they saw Ballarat!

The Aboriginal Connection

But that is not all of this brief history of Ballarat’s gold rush. The most important people that have often been neglected — until finally made known thanks to a digital tour on the museum’s website — are the aboriginals who owned the land. The Wadawurrung people, who lived in Ballarat, knew that there were plenty of gold to be found but they had no use of this precious metal in their own culture or economy. However, European gold miners were quick to convince the indigenous people to bring them to the gold, and soon, the aboriginals understood that the shiny yellow mineral was extremely valuable to the Europeans, and could be exchanged for food or money.

While for some aboriginal people, the gold brought a magnificent improvement in their lives, there were scores of Wadawurrung people who grew frustrated with the fact that these visitors were not leaving, and they were continuously taking from their land without compensating. Only a few Europeans believed that they had ownership of the land, while a majority didn’t.

But the Wadawurrung people did more than just lead the Europeans to the gold. They offered help, without which the miners wouldn’t have survived the Australian landscape. The aboriginals were eager to offer assistance to these visitors — apart from money or trade — as part of a cultural practice to develop kinship relationships between themselves and their guests, and as reciprocal gift-giving.

These included possum-skin cloaks that were thicker and warmer than woollen blankets and were effective in keeping miners alive through the chilling Ballarat winter, traditional foods such as eels and emu eggs, hunting as well as bush survival skills. They also shared Black Wattle sap, used by the aboriginals as a snack and cure for diarrhoea, to help treat dysentery among the Europeans. However, blinded by wealth accumulation, the Europeans saw trade as purely business and they failed to recognise any form of responsibility towards the Wadawurrung people.

With the increase in the number of diggers who arrived in hope of making big bucks out of the lucrative gold, the Gold Commissioner’s Camp was established. This was where miners were required to purchase Gold Licenses, which translated to permission to mine in the area. Those who dug without one were locked by the police here. Shortly after gold was discovered, the Native Police were the first troopers to arrive on the Ballarat goldfields. Upon the compulsory issuance of Gold Licenses, the Native Police struggled to maintain order on the goldfields. The troopers, comprising aboriginals from other parts of Victoria, gradually began deserting the force, often for their own pursuit of gold.

Also read: Whirlwind Side Trips from Melbourne You Won’t Regret Taking

It was these very Gold Licenses that formed part of the frustration among the Wadawurrung People who had to purchase licences to mine on their own land, and the expense of the licences and following taxation orders led the gold miners of Ballarat to revolt against the colonial authority in the United Kingdom. It was called the Eureka Rebellion, or the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, which the museum brilliantly portrays in its tantalising show ‘Blood on the Southern Cross’.

It is in the heart of the Wadawurrung People to offer land to its guests, and it is only an act of sheer gratitude and respect for these indigenous souls to shine an unforgiving light on the history of their vital involvement in the Ballarat Gold Rush today since history itself failed to acknowledge them.

And more history…

Visitors might find it odd to spot a Chinese Temple at the corner of the goldfield, like many of us did. But the temple marks a significant though small nugget of history. In the late 1850s, Chinese diggers who came down to Ballarat faced hostility from the European miners. Thus, they were forced to live under the care of a Chinese Protector. The temple is dedicated to a warrior God named Quan Gong, associated with peace, stability and prosperity.

The Chinese Camp, where the temple is located, is culturally Chinese indeed. A store situated in the camp is decorated with long red banners of Chinese Calligraphy and its counter is stacked with dim sum containers and traditional Chinese woven baskets. Garlic and chilli hung inside the store while an abacus lie untouched on a wooden table.

Outside lie gardens of freshly grown persimmon, among other vegetables, and a hot cooking fireplace made of logs and gravel in the middle of the camp. You can also find Chinese porcelain and calligraphy desks in Chinese miners’ tents, an indication that the Chinese had a piece of their homeland with them even when living on a foreign country.

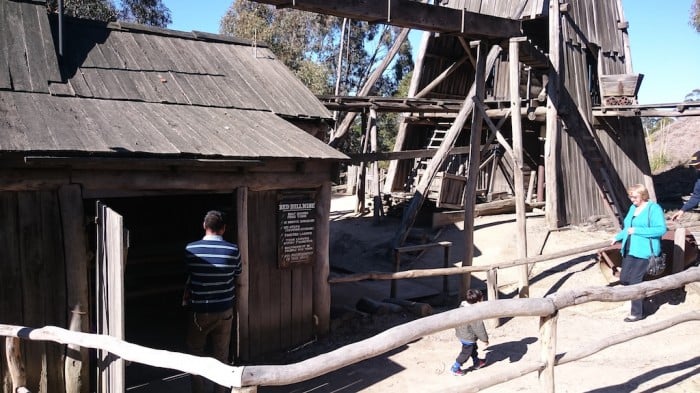

Now, if gold panning didn’t excite you much, don’t worry. There is definitely a chance to see some gold on this historic mining ground. There are exciting mine tours to embark on. The Red Hill Mine Tour is a self-guided tour underground, and it is free — which is probably why this shouldn’t be missed. ‘Mudlarks’, a name used to identify with the miners who dug deep into lead mines, which were cramped and deadly, ploughed through several layers of wet clay, sand and gravel to search for the precious yellow metal. The ‘Welcome’ nugget was found by 1858 by 22 Cornishmen, and the Red Mine Tour will let you explore how this 69-kilogram fortune was discovered.

On the other hand, the Gold Mine Tour is a fully-guided underground mine tour that covers three points of interests you can choose from — Journey Through the Labyrinth of Gold, Trapped and The Secret Chamber — and are priced differently for adults, children and family.

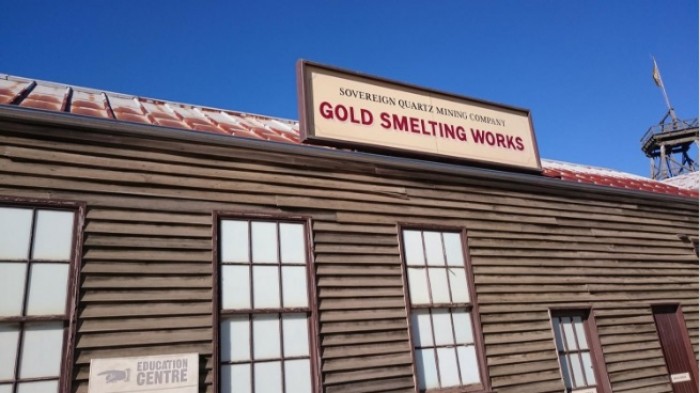

Mined gold, though it underpins the entire existence of gold on earth, is not exactly what you see in the market today. The final and dramatic stage is the smelting and pouring of the liquid gold into a bar that is valued today at around $150,000, though it may fluctuate. The Gold Smelting Works runs 15-minute shows at around half an hour intervals, and it’s hard not to laugh while still, at the same time, be awed by the entertaining goldsmith who effortlessly presents each step of the process. We witnessed the transition of molten gold to a deceivingly heavy gold bar.

Valued at around $170,000 while I was there, the bar put the workshop into the most vulnerable position, with many viewers plying their eyes on the majestic and highly prized spectacle. Some lucky ones got the chance to feel the bar in their hands, and after someone from the mesmerised audience shouted “run”, the man who held the valuable bar made a false try, only to leave everyone laughing. But what would have happened if he really did, I wonder.

Well, you don’t have the Redcoat Soldiers for nothing! Or rather, imaginatively.

Dressed in their distinctive bright red jackets that scream Britain in almost every aspect, these Redcoat Soldiers represented the original 40th Regiment on Foot. They were an infantry regiment of the British Army, tasked to maintain law and order on the Australian colonies, and also protect the gold that was being transported from Ballarat to Melbourne. They were also a key figure in putting down the armed rebellion during the Eureka Stockade.

The soldiers parade along Main Street at 1.30pm each day; their loud drums beating into the historic climate is sure to alert you of their arrival. After a series of commands from a Corporal, the Redcoat Soldiers load their muskets and take turns to fire, culminating in a loud bang that will make you jerk. Don’t worry, the Corporal will remind you to put your fingers in your ears, I’m not even joking.

Also read: 72-Hour Scenic Self-Drive Along Australia’s Great Ocean Road

And there are photo opportunities as well! There is indeed always something about uniformed men that catches the eye — fear and admiration — perhaps the latter is paramount for this one. *Wink* Oh, and a Native Police must be strolling around the area too, with his baton that complemented his classic navy blue uniform adorned with silver buttons. He walks in a suspicious manner, exuding the aura of a fierce policeman, especially when he taps his baton on his shoulders and freaking visitors out with his sudden appearance. But he’s a charm.

Trades, crafts and stores line the streets in their classic 19th century facade.

There is the candle dipping workshop at William Hewett’s Yarrowee Soap & Candle Works where you can make your own candle or buy several as souvenirs.

The Empire Bowling Saloon lies at the corner end, and if you have a strong arm, this ninepin bowling might excite you, just like how it did among the diggers on the goldfields.

If you stumble upon the Soho Foundry, you can see the machinery used to spin gold pans and brass candlesticks on a steam-driven lathe.

Or check out the fire engines that were sleek in style of those days!

Like I said, Sovereign Hill is huge; the amount of history embedded across the 25 hectares are in abundance and I can only advise one to move around slowly and perhaps read up before making a visit. And not to forget, your entry to Sovereign Hill ($54 for an adult and $24 for child, with family packages priced differently) includes the Gold Museum. It extends the story of gold from Sovereign Hill, depicting key events and figures from the Australian gold rush. Do check out the commanding view from inside the museum that overlooks the city of Ballarat.