While backpacking along the west coast of Taiwan, I take my friends on a 48-hour detour up Taiwan’s most well-known mountain range, Alishan to fulfil my bucket list wish of visiting a high mountain tea plantation.

The local TRA train pulls into the Chiayi station and a Mr. Wu picks us up. Together with his wife, they run the Mei Feng Jing Guan Min Su, a bed and breakfast nestled in a tea plantation along the Alishan mountain road.

On the way, he stops to buy two bags of fresh longan from a roadside vendor for us. They are sweet, rich, and cool, despite the summer heat.

The average height of the Alishan peaks rounds out at about 2,500 metres, and the car careens recklessly up the winding mountain road; a carelessness distinct to locals. As we climb higher and higher, the clouds fall below the cliff edges and the world falls into a hushed silence.

It has been raining intermittently all day, and the mountains are fresh with the scent of rain when we arrive. This stretch of mountainside is owned by the Wus, and as far as the eye can see, tea bushes sit in perpendicular.

After getting acquainted with our lodgings – a simple wooden room with bathroom included, and mattresses and blankets piled in a corner – Mr. Wu suggests driving us to a nearby town, Fen Qi Hu to explore, and informs us that the last bus leaves at 5pm.

While we are wandering among bamboo forest and creeks, another storm descends into the mountains. We are in the middle of walking pathways through old houses and trees when the dampness of spray mist and blanket fog roll in. It is so high up that the lower strata of cloud wets everything. Later, as we wait for the bus at a tea shop nearby, we order Alishan’s famous high mountain oolong, and for the first time, drink tea in its natural habitat, complete with the cool breeze, wet air and thick cloud.

We get off at the wrong stop on the way back, and as Mr. Wu drives out to get us, the rain pours maddeningly. We are caught in a tiny shop on the mountain highway with nothing between us and the storm save the weathered old tarp above our heads. The silence of the mountains is replaced with the deafening sound of hard rain on plastic.

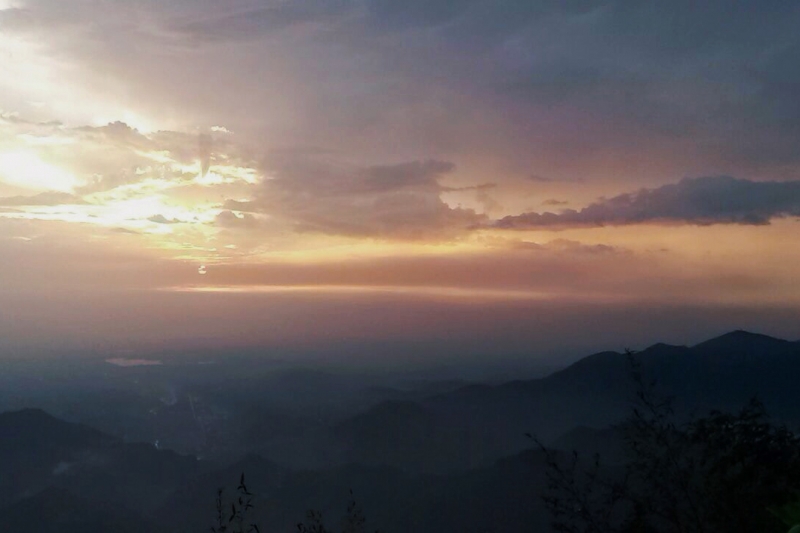

As evening approaches, the Wus recommend we hike up to a pavilion near the top of their plantation to watch the sunset. The storm has blown off and below us, dipping into the valley, the clouds are hurried along by the wind. They call this a “yun hai”; a cloud sea.

On that windswept mountain we stand on a rocky ledge, watching a sea of white flow beneath our feet, clouds slipping in and out of the peaks, the landscape wet with fresh storm. Everything as far as the eye can see is illuminated by old yellow light fading into evening.

It is a moment we don’t interrupt with our voices. The quiet of the mountain is so vast, it holds us.

At night the temperature dips to 10 degrees Celsius, even in the middle of summer. After dinner we gather around the huge wooden tea table for a round of evening tea tastings.

Mrs. Wu is the tea expert in this household, and steeps one of her higher grade high mountain oolongs for us. Apparently, it is strong enough to produce the same consistency of liquor for up to 14 steeps. She proves this by pouring round after round, golden liquid flowing from teapot to smelling cup, to tasting cup, to our lips, into our bodies. She reminds us to inhale; to allow the liquor to flow across the tongue; to recognize the strength of the leaf.

Four hours later, I am still conscious of my fluttering heartbeat on the mattress floor.

I hover somewhere between deep sleep and caffeinated stirrings, listening to the sound of mountain nights, never silent, but always quiet.

I hear expanse of rock swallowing up the wind, deep-throated frogs squatting by the wall, and thrilling insect song.

I also hear the deep breathing of sleeping roommates: less sensitive to caffeine, more exhausted.

I get up first in the dark morning, having given up on good sleep. Mr. Wu is smoking by the car, waiting impatiently to take us to what, in his opinion, is a better lookout spot than the famous sunrise viewing platform in the Alishan National Forest Recreation Area. He tells us repeatedly as the rest shake sleep clumsily from their bodies and climb into the car, “If we don’t hurry we’ll miss it. We’ll miss it.”

We don’t however. It is a spectacular sunrise, but in the understated way of Alishan. It rises and breaks the cloud cover with no hurry, drifting lazily above our recent hectic journey to meet it.

First light infuses the air with a dust yellow sheen, turning the dark side of the mountain into hues of greens and browns. As far as my eye can see, rows and rows of tea bushes circling small houses, cascade in perfect rows down into the valley.

We wait till the sun lifts its body proper out of the peak line, before packing ourselves back into the car. Mr. Wu drives us to the Alishan Recreation Area, bidding us farewell in the same gruff manner he greeted us.

We spend the rest of the morning and early afternoon hiking old trails in the shadow of the giant sacred trees, thousands of years old. The national park is full of people, but even here, the mountains pull sound into rock and wood.

A new storm begins to roll in and so we head out to the bus stop, to ride the coach bus two hours back down into the city.

On the way down, the lightning streaks in clear flashes cliff side, the bus speeding down the road with the same carelessness as Mr. Wu’s car.

Just before I fall into the deep sleep that wouldn’t come the night before, I mutter a short prayer to survive the wide ride. Outside my window, the mountain peaks, snarling with thunder and grey cloud, are quiet nonetheless, and slowly recede.